The Sexuality Spectrum

by:

Ger Moane

Published:

Tuesday, May 5, 2015

We often describe sexuality in terms of gay or straight or bi, as if these are fixed categories that are each very different from each other. But what exactly do these labels mean? Are gay and straight really the opposite of each other? This article is based on a recent Soul Seminar in which I aimed to explore these questions in a lighthearted and hopefully illuminating way.

These kinds of questions have long been topics of conversation, especially among lesbian and gay men who were questioning sexuality. Up to recently, discourse about sexuality was dominated by biological and religious views that said that procreation was the purpose of sex. This assumption was the basis for Catholic Church teaching that said sex should only happen in the context of marriage and for the purpose of procreation, and for the Catholic Church’s opposition to contraception.

The Catholic Church, the medical profession, and society generally took a very negative view of homosexuality. Until 1973 people could be send to psychiatric hospitals because homosexuality was a listed psychiatric condition in DSM (The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual used by psychiatrists and psychologists). In Ireland homosexuality was criminalized until 1993.

This condemnation made it very difficult for people to question sexuality or consider that they might be lesbian or gay. But it didn’t prevent people from coming out, or stop many of us from challenging society’s assumptions about sexuality. Narrow definitions of sex as involving sexual intercourse for the purposes of procreation just didn’t fit with many people’s sexual experiences.

Sex involves much more – pleasure, emotional connection, relationships, fantasy, and spirituality to name a few! The sexuality spectrum involves this broader view of sexuality.

When psychologists started doing research about sexuality they quickly ran into a problem – how would they ask people to identify their sexual orientation? People were simply asked to pick “heterosexual” or “homosexual”. Yet researchers and clinicians noticed that many people who did not identify as homosexual (or as gay, lesbian or bisexual) had same-sex sexual experiences, and that many who did identify as gay or lesbian had heterosexual experiences. This raised the question of what sexual orientation actually means.

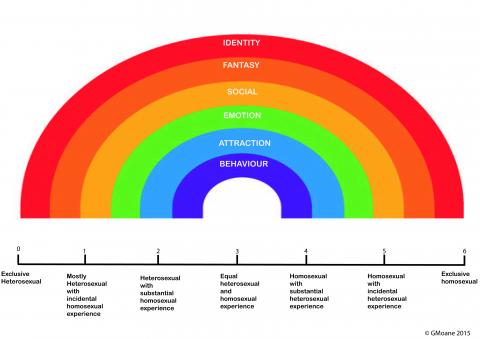

As far back as the 1950s Kinsey had proposed what he called ‘the sexual continuum’, based on people’s sexual experience. He created a 7-point scale with exclusively heterosexual at one end (point 0) and exclusively homosexual at the other end (point 7). Exclusively heterosexual meant that someone had no homosexual experience. Exclusively homosexual meant that someone had no heterosexual experience. In between were points representing a mixture of heterosexual and homosexual experience, with the middle (point 3) as ‘equal heterosexual and homosexual experience’. General surveys of sexual behaviour still tend to ask respondents to choose straight, gay or bisexual, but more detailed research, and clinical research, often use the Kinsey scale. These studies have found that many people have same-sex experiences and still identify as heterosexual.

When researchers started using the scale, a question quickly arose. What exactly does ‘sexual experience’ mean? First of all, it could mean anything from kissing to full orgasmic sex. But even that only refers to actual sexual behaviour. What if you fall in love with someone of the same gender but don’t have sex? What if you have sex with someone of a different gender but don’t fall in love? What if you fantasize about a different gender from the one you’re having sex with? What if you have a primary relationship with one gender, but casual sex with the other gender?

Psychologists use the phrase ‘multidimensional’ to refer to this idea that there are many aspects or dimensions to sexuality, and a psychologist called Klein proposed a grid to measure this. I prefer the phrase ‘sexuality spectrum”. The sexuality spectrum incorporates these aspects of sexuality as well as the sexual continuum – and this can make things much more complicated, but hopefully more fun as well! This image tries to capture the sexuality spectrum. Each person can score themselves on the Kinsey scale (from 0 to 6) with reference to the different aspects of sexuality.

Behaviour or experience refers to actual sexual experience (and you can be broad or narrow in your interpretation of behaviour!). Attraction refers to chemistry – with whom you have a sexual reaction (still one of the mysteries of sexuality). Emotion involves feelings of closeness, intimacy and passion (again this can be interpreted broadly or narrowly). Social refers to who you are drawn to socially. And fantasy refers to which gender(s) are present in your sexual fantasies. Finally, identity refers to how you label yourself. Many people who are primarily heterosexual have not really thought about this, partly because heterosexuality has been taken for granted in society.

There are plenty of people who will score consistently across these dimensions and there are also plenty who will be at different points for the different dimensions. For example someone might have no fantasy or desire for the same gender but might still have had a sexual experience. Someone might have sexual experience and intimacy only with the same gender, but experience attraction to the other gender. Many people have fantasies involving threesomes, or where they role play a different gender from their own.

There isn’t an exact fit between the different aspects of sexuality, which are represented in the rainbow, and the Kinsey scale; this is just a fun exercise to illustrate the sexuality spectrum.

As if this isn’t complicated enough, we have to bear in mind that the sexuality spectrum isn’t static, it can change over time! People can change over their lifetimes in terms of where they are on the different aspects. A good example of this is people who come out as lesbian or gay late in life, in some cases after having had a loving committed heterosexual relationship.

Additionally, culture has a big influence on sexuality and on how people experience different aspects of sexuality. In Ireland, for example, there has been much social change and more acceptance of gay and lesbian sexuality and of bisexuality. A recent article in a popular magazine pointed out that sex stopped being about procreation a long time ago and proposed doing away with heterosexuality and homosexuality, calling for ambisexuality – doing away with labels and having sex with the most appealing person. The word ‘queer’ is used, especially by younger people, to indicate this refusal to be categorized, and also to call into question hetero-normative assumptions about sex and sexuality.

All of this offers a more dynamic and fluid model than the old medical and religious models. Sexuality involves the whole person – mind, body and spirit. Even though these developments mean a more open society, there is still a lot of homophobia in Irish society – for example bullying in schools, physical assaults, “that’s gay” as a put down, difficulties coming out, especially to parents. And a substantial number of people are opposed to lesbian and gay couples being allowed to marry each other and have the same legal and social protections as heterosexual couples.

About the author:

Ger Moane is a psychologist, writer and shamanic practitioner. She provides education, training and workshops in the area of sexuality, and has recently been involved in developing Guidelines for Good Practice with Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Clients for the Psychological Society of Ireland. She has trained in counseling and in groupwork and has had a practice for 15 years. She lectures in psychology in University College Dublin and has published on gender and sexuality as well as on ancient Ireland and the Irish psyche.

Ger Moane is a psychologist, writer and shamanic practitioner. She provides education, training and workshops in the area of sexuality, and has recently been involved in developing Guidelines for Good Practice with Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Clients for the Psychological Society of Ireland. She has trained in counseling and in groupwork and has had a practice for 15 years. She lectures in psychology in University College Dublin and has published on gender and sexuality as well as on ancient Ireland and the Irish psyche.You can contact Ger at: [email protected]

In Issue:

Latest Issue

Upcoming Events

-

17/04/2020 to 26/04/2020

-

18/04/2020

-

23/04/2020

-

15/05/2020 to 23/05/2020

-

16/05/2020 to 17/05/2020

Recent Articles

Article Archive

- May 2017 (4)

- June 2017 (11)

- July 2017 (7)

- August 2017 (2)

- September 2017 (1)

- October 2017 (3)

- November 2017 (4)

- December 2017 (3)

- April 2018 (2)

- June 2018 (2)