Neurosculpting - How we create and replace memories

It is a difficult pill to swallow when we are told our memories are only partly accurate. Memories are the anchor points of our own biography. They are the historical marks that put us at places in time with others, creating a web of interactions that hold together the story of who we are. We wear memories like badges, using them as guideposts or roadblocks. Each memory’s trail creates life sculptures in the folds of our brain as we neurosculpt our reminiscences. Our identities are so wrapped up in our memories that we sometimes don’t realise if we could just loosen that grip a bit we could be a bigger or better version of ourselves. Stepping into our greatness involves recognising the past, and then contextualising it in a way that allows us to grow into our present-time self fully.

As humans, we seem to be obsessively focused on the part of our lives that already happened rather than the parts that are happening right now. We look at photos to reminisce. Good friends often drift into reverie around the good old days. Parents try to hold on to memories as children grow up, slipping like sand through Mom and Dad’s fingers. We reference memories of past injustices each time we meet similar circumstances. We hide behind images of long-ago days, and we mourn those who lose their ability to remember.

So what is this hold that memory has over us? And can neurosculpting give us back our power over ever-changing phantoms of what life used to be? To be clear, our memories and past events have made each of us who we are in this moment, and for that I find it easy to be grateful. But for a long time I was unable to be in the present moment, unable to take in more of life because I filtered my experiences through outdated beliefs. Living in the present moment allows us to respond appropriately to situations with access to our full emotional spectrum rather than reenacting a well-played script for which we’ve already assigned our affected behavior.

I’m not suggesting we forget our pasts or deny the events of our lives. However, many of us keep pulling up the lens of our memories, and we use that lens in the present moment to filter life’s experiences. I am suggesting that we honor the past by saying thank you and allowing it to retire into an area of our minds we can reference at any time but that does not cloud our present vision.

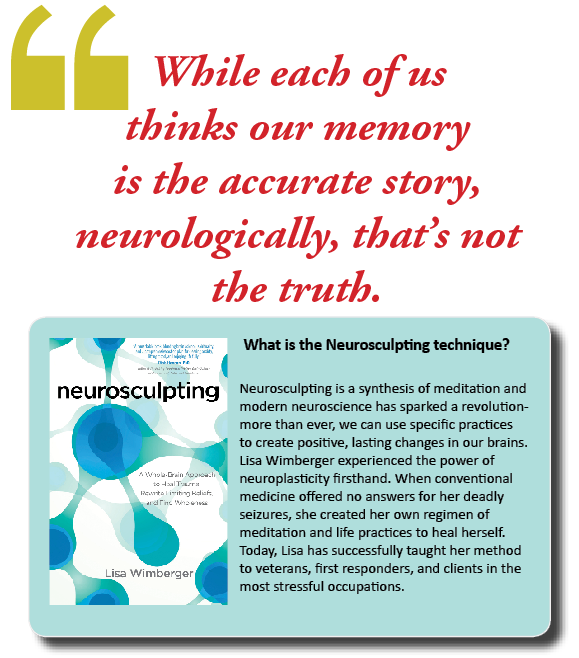

While each of us thinks our memory is the accurate story, neurologically, that’s not the truth. To create a lasting memory the brain needs a few things in place. It needs to pay attention, and it needs an experience upon which to focus that attention, even if that experience is only in the mind’s eye. It seems that our levels of attention during the experience are the critical factors in whether or not that event becomes well established in our memory. Because there are many different cortices of the brain involved in experiencing our reality, our memories are actually encoded as a synthesis of different parts or a construction of separate pieces. And the glue of this construction is focused attention.

Think about this scenario: if you are in a lecture or class, and you are distracted by some intrusive thoughts, remembering an argument you had that morning, multitasking on your phone while the teacher lectures, and shifting in your seat often because you are physically uncomfortable, you will remember far less of the lecture than if you paid full attention. Splitting attention uses valuable resources in areas other than to take note of the events we want to store in our memories.

What is happening during those moments of full attention that allows an experience to be embedded?

Generally, moments of heightened attention correlate to a particular sweet spot of neurotransmitters in the prefrontal cortex. Consider the analogy of a radio. When we want to tune in clearly to our favorite station and then program that station in, we need to lock on to the signal and simultaneously inhibit outside static, then commit it to a particular dedicated button. This is similar to what our neurotransmitters do when we are paying attention. Some of them, like norepinephrine, amplify the relevant signal while others, like dopamine, inhibit irrelevant static or distraction. And still others, like acetylcholine, help glue in the experience we’ve locked onto for quick and easy reference. So when we feel ourselves paying attention, we are feeling this well-orchestrated harmony of stimulus amplification and inhibition of distractions.

There’s yet another critical piece of this process that has the power to turbo-boost the glue of the newly forming memory, and that’s our emotions. The more intensely we feel an emotion during the experience, the more attention we pay to the experience and the more deeply we embed the memory.

Fear is one of the strongest mapping emotions. Maybe this is an evolutionary gift to keep us from putting ourselves in harm’s way too often. A good jolt of fear during an experience has the power to make that memory last an entire lifetime. Sadly, the more we use fear as a lens through which we view the world, the more fear makes a home in our memories. And if we layer version on top of version in our memories, the fear charge can bleed through to all other memories. This comes with the associated rise in stress hormones, contraction, and impaired digestion and cognitive functioning.

The process becomes even more complex as stress hormones impair our ability to relax. What science is now finding is that a period of brain rest after an experience is vital to our ability to store that memory more deeply. Remember, the hippocampus is an integral part of creating and storing our memories and is easily damaged by these very same stress hormones. This part of the limbic system plays a critical role in the creation of the episodic memory, but the storage of this memory over the long term involves translating the experience across to other structures of the brain, like the neocortex.

It’s not all bad news, though. Fear may be one of the strongest emotions in the process of embedding a memory, but fortunately it’s not the only one. Novelty can hijack a moment, just like fear can, and cause us to pay full and heightened attention. Consider this example and you’ll instantly understand the power of novelty in the memory process: Imagine you are in the same lecture as earlier—distracted and multitasking. The teacher’s voice washes in and out like a droning hum. Suddenly, a miniature, three-inch purple baby elephant walks in to the room, stands in front of you and sneezes—the most adorable sound you’ve ever heard. What do you think the one thing is that you will remember from the lecture? You will likely remember the elephant indefinitely because it was a moment of total novelty, an unexpected yet nonthreatening stimulus that hijacked your scattered attention and recruited a moment of harmonizing neurotransmitter activity in the front of your brain. Your mind likely made you feel a moment of “huh, what’s that?”

Now pretend you have a choice for a moment. Would you rather commit the vast majority of your life’s experiences to memory through fear or novelty? Once you’ve answered, understand that you do have a choice. Intentionally choosing moments of novelty over fear is possible with practice and dedication. The truth is that it’s what we pay attention to and the way in which we choose to pay attention that defines the treasure chest of our biographical memories. And we can also lose our ability to retrieve a memory if we first experienced the moment in a state of divided or partial attention. So it’s in our best interest to cultivate a practice and disposition that seeks to reframe an over-reactive fear response to one of curiosity and novelty.

Creating memories is a practice that can be gently guided and self-directed. You are the true author of your biography.

Lisa Wimberger is the founder of the Neurosculpting Institute and author of ‘Neurosculpting: A Whole-Brain Approach to Heal Trauma, Rewrite Limiting Beliefs, and Find Wholeness’ and ‘New Beliefs, New Brain’. A member of the National Center for Crisis Management and other care associations, she has a private practice in Denver, Colorado, specializing in helping clients with stress disorders. For more, visit www.neurosculptinginstitute.com

Latest Issue

Upcoming Events

-

17/04/2020 to 26/04/2020

-

18/04/2020

-

23/04/2020

-

15/05/2020 to 23/05/2020

-

16/05/2020 to 17/05/2020

Recent Articles

Article Archive

- February 2016 (3)

- March 2016 (2)

- April 2016 (2)

- May 2016 (3)

- June 2016 (1)

- July 2016 (1)

- January 2017 (6)

- February 2017 (4)

- March 2017 (11)

- April 2017 (9)