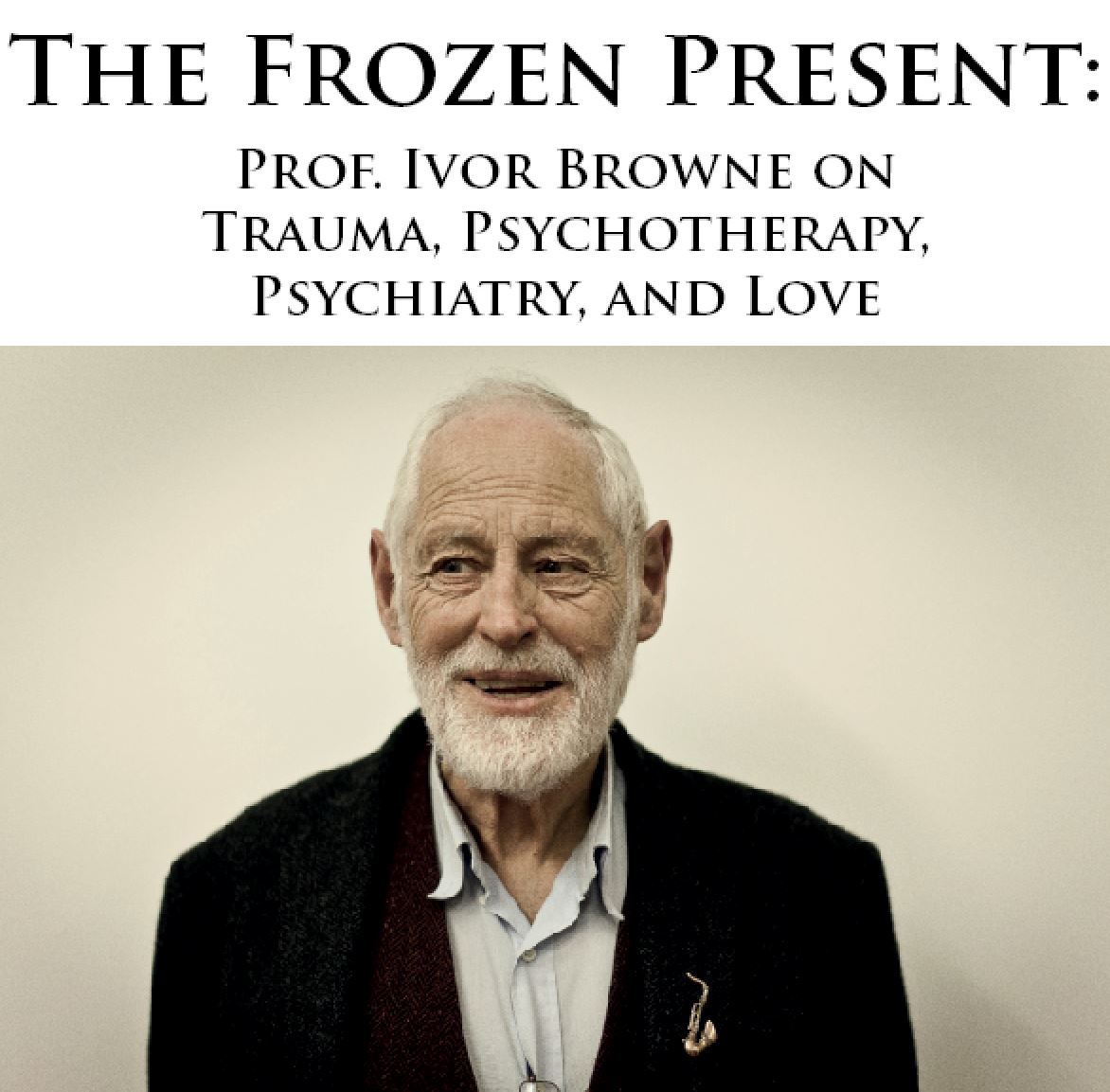

Ivor Browne: The Frozen Present

Walking to meet Ivor Browne on a sunny morning in Milltown in Dublin, I’m reminded of the old TV game show Supermarket Sweep. I can empathise with the frantic families and their predicament of navigating seemingly infinite aisles of goodies with very limited trolley space. At 85, the Professor emeritus of psychiatry at UCD has an unprecedented level of experience in the world of psychiatry and psychotherapy. Renowned as someone who is not afraid to rock the boat when needed, we spoke about the need for more discussion around trauma, psychiatry, and psychotherapy in Ireland.

Before we talk about it, we have to be aware of how we talk about it, as this can be problematic, explains Ivor. ‘A lot about how we process trauma is not understood correctly because of the way we use language’ he says, ‘people have become so used to the Freudian idea of repression, and we have this misunderstanding that experiences automatically become memory . But the reality is that it can take a hell of a lot of work. Experiences, like our conversation now, pass through the limbic system, a primitive part of our brain. Ordinary things go through it quite quickly, but if you have something very threatening or traumatic when it hits that area of the brain it fires the body. That is the way we are constructed through evolution. We recognise threat by what we feel. Sometimes what we feel can be so great that the message comes back saying “shut down, I cannot handle this”.’

The Frozen Present

How we understand the impact of trauma is of vital importance to how we can work with trauma, so Ivor’s idea of ‘the frozen present’ becomes a key part to understanding how he looks at psychiatric and psychotherapeutic work.

‘Once that shut down happens, then that experience is frozen. So it is not a case of a threatening memory being repressed, it is that it has never gotten in properly. Once it is frozen it is outside of time, so twenty years later this can be activate - some everyday event can trigger it – and you then experience it as if it is happening now. You don’t think about it and remember it - you feel it and experience it. And of course at that point you think you are going nuts because you look around and nothing traumatic is happening, yet you experience this traumatic feeling. That is why I called it “the frozen present”, because when it comes, it comes through as the present, not as the past. Eventually when it works its way through and you experience it a few times then it moves into the past.’

‘The best example is grief’ Ivor says, ‘if you have lost someone you have to do a lot of work over time in order to integrate that to allow it to become a memory. Then it becomes less threatening. When my wife died five years ago, the first year was absolute hell, and I couldn’t imagine feeling any joy. The second year was bad, but not quite as bad as the first. Now after five years I am quite contented. I have a different life.’ By processing the trauma, it has shifted into memory, but this approach is not possible in the current psychiatric model, Ivor suggests.

Trauma in the psychiatric model

‘Psychiatry is a reductionist system that explains everything by the parts. The important thing about explaining things by the parts is that it is not wrong. There are a lot of ordinary things in life that work like that. If your car is not working, you check and see what part is not working. When you damage or break your hip, you need to look at what part of the mechanism is faulty and it can be replaced. But the trouble with applying that outlook to life at large is that it doesn’t cover the whole question. So it is not to say that it is wrong to think that way, but it is about knowing when it is appropriate and inappropriate to think that way.’

‘The tragedy of psychiatry is that this is the only way you can think. Because in the psychiatric model you cannot ask how the behaviour or upbringing of a person is effecting their biochemistry – you can only ask how is the biochemistry effecting the person. Psychiatrists don’t take a history, so they don’t understand the problem in the context of the individual’s life. They put a label on, and then they say you need medication. So the person is already defending themselves against whatever label they have been given, and then the medication can further dampen things down. Often this is the exact opposite of the help that they need. The whole of medicine and orthodox science works through the reductionist model, rather than a holistic model. That is an essential difference there between the psychiatric and psychotherapeutic models. In psychotherapy you are giving the person a safety net in which they feel comfortable enough to open up the trauma, in psychiatry you are giving a diagnosis.’

‘I’m not against diagnosis, I think it is vital. But the diagnosis you need is the diagnosis of the person and their whole life. Whereas what they are doing is taking a few symptoms and putting a label on them - which is just an illusion. But this approach is very appealing in society because we are accustomed to understand things through a reductionist, mechanistic framework, and that involves labels and remedies.’

‘The principle of life is that we are self-organising. We keep ourselves in existence. Ultimately the individual needs to take back control, and that means you need to manage your own health. If someone goes for surgery, the surgeon intervenes temporarily but once the person leaves the care of the hospital the onus is on the individual to live their life accordingly. But we can easily develop a dependency; we can think that the answer lies with the other. This applies to psychotherapy as much as psychiatry.’

Trauma in psychotherapy

While Ivor continues to practice psychotherapy, he is keen to point out that the psychotherapeutic model carries across some unhelpful reductionist assumptions. ‘The very title – therapy – suggests that it is something that the therapist does. That is probably the deepest falsehood in the whole thing, the notion that we, as therapists, have treatments that we can do to people. The reality is that the person does the work. If the person is not prepared to do the work of change, you can be the greatest therapist in the world and you cannot do anything. I don’t think we can apply normalising elements – like ideas of the ten session model - to psychotherapy. Each person will react differently. People that train as psychotherapists – which psychiatrists don’t remember – learn about their own life difficulties by going into therapy themselves. Essentially the relationship in psychotherapy is heart to heart. The person therefore feels protected and safe enough in the relationship to do the work. There is a paradox there because quite a lot of psychotherapists, while they have had good training, have not had the experience I have had in dealing with what we call madness – like going into closed wards where people might suddenly take a belt at you. So in some situations the therapist may be afraid that if the situation blows up they might not be able to handle it. And of course the person picks that up so they refuse to open up.’

‘So the first aspect is that the person feels safe enough in themselves that they can do the work. And the even more important second aspect is they feel that the therapist is safe enough to handle whatever might come up. I didn’t realise the second aspect for a long time because I assumed therapists were not afraid, but a lot of them were scared because they had not had any experience with psychosis.’

The therapeutic relationship

‘Carl Rogers was essentially right with his idea of “unconditional positive regard”. In many ways I think his work has been misunderstood and has become about comforting the person – but understood properly it is the basis of therapy.’

‘You can divide therapy into two halves – the first half is opening up the relationship. This involves allowing the person to open up their defences, so in a sense they become much more vulnerable, and in this stage they can become dependent.’

‘And as they go through it then the second half is about helping them to bring themselves together again, and finding what Frankl, and Jung, and Adler talk about – finding the direction and goal that they need to pursue to realise their life, and they become more independent. Sometimes therapists want to jump to that second phase without doing the work, the painful part. That is where I think Freud deserves some respect because he kept his snout in the trough with the family and the core relationships. Unless the person brings that in and works it through, it is unlikely that they can on to the second part.’

‘Once people feel safe they can work through their trauma a lot easier. I still use some regressive methods but more and more I find that it is about reaching a point with the person where they feel safe to do the work, and then they will open up the same thing. It doesn’t matter what way you find to do that – you can use art and image work, or shamanic work, or regressive methods – it is whatever helps the individual to open up, to get to the final common path which is where the person can activate and bring out the experience. People often relate the length of therapy to the depth of therapy. But it doesn’t work like that. You can be ten years in analysis and still be asking – “when does the cure start”, or you can hit it in one sitting if the person feels safe enough to open.’

The deepest trauma

From Ivor’s perspective, experiencing trauma is a natural part of being human. ‘Everyone will have some trauma to go through in life but, so it is like filling a container. We can manage to contain a fair bit and get on reasonably well, but when we have one bad thing backing up on another then at a certain point, it overflows. You find that a person may be able to contain one grief, and then another one, but then a final one occurs and that is too much for them to contain and it all opens up. When that happens it is overwhelming, but from a positive point of view that means that they can not only resolve the recent trauma, but it is also an opportunity to resolve the earlier ones.’

Key to processing trauma is cultivating a relationship that allows it to be processed, and that ultimately involves love, and the deepest traumas we can experience involve a separation from love. ‘The deepest wound of all can be of someone who is rejected at birth – it can be down to any number of reasons, but in effect, if the mother doesn’t want the child then the child starts life from conception on without any understanding of what love it. This can happen in a family where there doesn’t appear to be much trauma. The grief of not being loved is very deep. Not only is the person traumatised but they have to learn about love from another relationship.’

‘The truth of all this is that the heart is the centre, and if our heart is closed we cannot experience love. At this moment there may be thousands or millions of messages and information passing through this room, but my iPhone may only be able to activate one of them – which is an extraordinary miracle in itself – but imagine if I could access more of that data. In the same way, there can be a lot of love around you in the world but you might only be able to access a very limited amount. if your heart opens, then you can connect. Distinct from religion, that is what all the mystical traditions say. It is all about love. Francis of Assisi, for example, not only loved other people, but he loved all animals and other species as well. This is where we are failing – we think we are the most important species but we have no more right to exist that anything else.’

As the afternoon draws to a close, I realise that many items on my Supermarket Sweep shopping list remained unchecked. But I’ve got some unexpected treats in the trolley – though our discussion just skimmed the surface of an immense career, it also plumbed some depths. I felt as if I had followed a thread running from that outward psychiatric model focused on symptoms and treatment, to that inward labyrinth of suffering and a search for meaning.

‘These are the kind of things that we can talk about through poetry, or through the therapeutic model, but we can’t deal with these concepts through the psychiatric model’ suggests Ivor in closing, ‘at the deepest level, a lot of our problems are spiritual.’ I’m left with the thought that perhaps Ivor was right when he suggested that the way we use language can cause the problem. If our deepest problems are indeed existential and spiritual, then we have very few ways to express these – it is not that we just need words and forms of expression, but words and forms that carry sufficient weight and value in our society. It may not be a case of providing diagnoses and solutions to our deepest problems, but rather expanding our lexicon and changing the way we understand them.

Latest Issue

Upcoming Events

-

17/04/2020 to 26/04/2020

-

18/04/2020

-

23/04/2020

-

15/05/2020 to 23/05/2020

-

16/05/2020 to 17/05/2020

Recent Articles

Article Archive

- November 2011 (2)

- January 2012 (3)

- February 2012 (2)

- March 2012 (2)

- April 2012 (4)

- May 2012 (4)

- June 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (3)

- August 2012 (2)

- October 2012 (2)