Growing in the dark - some lessons from depression

I felt a funeral in my brain

And mourners to and fro,

Kept threading – threading – till it seemed

Sense was breaking through–

I remember before I felt these things. I remember looking at my sister in her darkened room in the depths of emotional turmoil. I remember looking down that hallway and hearing endless sobs and I remember bewilderment. What was so wrong? Why was my sister feeling so much pain? I thought everything was kind of ok. But it wouldn’t be long before I felt it too. Like Emily Dickenson and my sister I would soon come to know the funeral in my brain.

There is a silent disease sweeping the land. The latest figures suggest 300,000 people in Ireland are suffering from it. It hospitalises 10,000 and contributes to the deaths of 400-500 Irish citizen’s year on year. Don’t panic - it isn’t contagious, it’s not the dreaded Ebola, that awful mutilating illness that took the life of no Irish citizen ever. Although that said, you are eight-times more likely to catch the disease if your parents suffered from it. This of course places considerable strain on the word ‘contagious’. Mysteriously, two-thirds of the people who suffer from the disease do not seek help for it, instead they suffer from its chief weapon; silence. But things are changing. The message, ‘It is ok not to be ok’ is getting out there. The awful crushing silence is beginning to erode. But is it enough? How is the vocalisation of depression helping the depressed? And perhaps most importantly, is it bringing us closer to a cure? Or is there such a thing?

I have suffered from what we term ‘depression’ for most of my life. I am 38 years old and was first treated for depression and severe anxiety at 22. When I took medication for the first time it provided some relief from what can only be described as a kind of living hell. Panic attacks left me curled in corners afraid to move or woke me in the night like demons. Fear became my permanent state. When anxiety had wrung me through, and I believed it wasn’t humanely possible to feel any worse, depression came. The mourners then, threading to and fro on my limp corpse-like existence.

Depression feels somewhat like the life has been sucked out of your body, as if something alien came in the night and took it from you. Movement becomes akin to death. Even the smallest task seems gargantuan; a monstrous act promising some kind of annihilation.

After depression had taken hold I was left swinging pendulum-like between two unbearable states. At one pole fear and its great force sent waves of fierce energy throughout my body. Eventually that energy sent me back upon myself, back past equilibrium toward collapse and capitulation and to depression once again. It was the kind of awfulness that underpins Sartre’s description of existence, ‘I exist’, he bemoaned, ‘that is all, and I find it nauseating’. Like Sartre I began to experience life as some kind of sickening curse. I’d stand on platforms with my back pressed to walls. Far from steel just in case the urge for an end came on too strong. When relief arrived in the form of anti-depressants I realised I had been feeling the edges of depression since I was a child. I can trace its lurking shadow backwards to my tenth year.

My treatment continued into my mid-twenties when symptoms lessened and my nervous system settled from being a frayed conductor of currents of pain. After a period of wellness, which was preceded by months of therapy and medication, my GP decided to take me off the drugs. Within six months I relapsed into a severe depressive episode. Strangely I found the relapse more intense, more painful. Usually a second bout of pain is easier no? Surely experience, objectivity, understanding would contribute to a lessening? With depression I have found the opposite to be true. Logic, and all the rational human tools disappear into the black hole of the depressed mind; the more depressed you get, the more depressed you get, so it seems. I think the worst thing depression does is it tears at your innate sense of belonging. The one that says, “I am safe here, this is where I am supposed to be”. The fabric that bonds us to the human form is stretched, misshapen and then sometimes torn. The world becomes a foreign hurt-filled place, and the very ground of our being is confronted. In some cases, it obliterates that ground, flattening us in the process. Depression feels to me like an illness of vitality, an illness of will, rather than solely a mental one, and it challenges that will and that vitality and all the other innate human functions we take for granted to their very limits.

Throughout the last fifteen years I have been living with depression many questions have arisen. Insights and answers have appeared sporadically, often providing illumination to darkened corners of misunderstanding. Many questions however remain unanswered. There is one which stubbornly refuses to leave. It returns through wellness and in the pitch black, and it hovers in a constant as if asking to be answered. I believe most people who face serious depression also ask themselves the questions: Is depression an emotion, or is it a disease? Is it something that must be treated medically, like diabetes or asthma? Or is it as a result of life? An emotional precursor for growth perhaps? A thing to be faced, passed through, transcended. Like the mythological phoenix a dissolution of self before birth anew. In attempting to answer these questions I have realised numerous things. One of these is that the modern bio-medical treatment for depression can be effective at alleviating symptoms and bringing function back into our lives, but that long term it is not a cure. Some of the medications used to treat serious depression have addictive qualities, and most have extremely harsh side effects. In my experience long term use of these medications can often inhibit our ability to recover fully from depression.

Depression affects both mind and body. Depressed thinking brings about depressed emotions which affect the body. These emotions cause physical responses which in turn fuel depressed thinking, and so on. Like a mouse on a wheel depression acts as a vicious cycle between body and mind. Medication can change our mood receptors which has a knock-on effect to thinking which can break the cycle, albeit temporarily. In my experience, and I believe in the experience of many others, when medication is discontinued the depressed thoughts often return to begin the cycle again, and invariably the old thinking, the old patterns of pain return. This is perhaps reflected in the recurrent nature of depression. 50% of those who recover from an initial depressive episode will have further episodes in their lifetime. This rises to 80% after two episodes, the more depressed we get, the more depressed we get! Or so it seems.

To treat depression successfully, and just not temper it, we must address our patterns of thinking as well as our physical symptoms. We must do this because the mind is boss, and the body believes what the mind says, acting out the intricacies of our 90,000 a day thoughts. Mind over matter is an old adage and one which is apparent in the confounding effect of placebos, but a fact that the medical industry refuses to fully embrace. I often wonder could the answer to this denial lie somewhere in the quagmire of the billions and billions of pharmacological profit that that arise from the commodity of the ‘sick’.

In a sweeping investigation into the efficacy of anti-depressants entitled The Emperor’s New Drugs: Exploding the Antidepressant Myth, author and Harvard medical lecturer Irving Kirsch, used the Freedom of Information Act to obtain FDA reviews of all placebo-controlled clinical trials (positive or negative) that were submitted for the initial approval of the six most widely used antidepressant drugs approved between 1987 and 1999—Prozac, Paxil, Zoloft, Celexa, Serzone, and Effexor. The results were startling. Altogether, there were forty-two trials of the six drugs. Most of them were negative. Overall, placebos were 82% as effective as the drugs. In another recent book investigating the astonishing rise of mental illness in America, the author Robert Whitaker not only agrees with Kirsch’s contention but contends that anti-depressants can cause damage to the neurological structure of the brain. With long term use, Whitaker suggests, it becomes almost impossible for the sufferer to discontinue medical treatment, as the drugs themselves effectively change the neural pathways of the brain making the user neurologically dependent upon their effects. Despite the new wave of research which is suggesting long-term anti-depressant use is inhibitive to recovery medication is still most often the only approach a GP will offer in response to depression. This is despite the fact that serious depression is often difficult to diagnosis.

The increasingly problematic modern world and our culture’s lack of tolerance of emotions can often complicate a diagnosis of depression. For instance, reactive depression is clearly distinct from serious depression and is a natural human reaction to trauma, to grief, to loss. In a culture where there is so little wisdom concerning human emotions, often people who should be treated aren’t, or those who are treated medically could do without the harsh repressive realities of a medical intervention, instead benefiting from a more holistic approach to their treatment. In this light it is easy to come to a conclusion that our current social, cultural, and medical model for treating depression is deeply flawed. This is not to say that some GPs are doing great work in their efforts, but it is to say that they are unequipped to deal with depression in a way that can allow the sufferer a possibility of overcoming the disease.

I believe our current approach to treating depression is wholly inadequate and ignores the idea of a cure. It condemns sufferers to a life of taking extremely harsh medications, in the process swelling the coffers of pharmaceutical conglomerates. We are failing to cure depression because we are failing to address depression at the level at which it exists. Because depression presents as both a physical and a mental disease its symptoms, treatment and recovery require both a physical and mental approach. One may argue that the contemporary method to treating depression is certainly an improvement on the barbaric practices of half a century ago and beyond, where people were incarcerated and subjected to treatments that wouldn’t have been amiss at Guantanamo. However, it is my experience that when serious depression is treated through medication alone we can become somewhat like our ‘insane’ ancestors; except now the prison exists inside. We become cut-off from the very emotions that can be our cure. When I began to confront the thoughts and emotions associated with depression true change began. When I faced these seemingly terrible things inside of me what I found was nothing short of profound.

And, then a plank in Reason, broke –

And I dropped down, and down

And hit a world at every plunge

And finished knowing – then.

When I read this last stanza from Emily Dickenson’s poem I imagine her reciting it alone in her room amongst her hardest days in the cold and bleak Massachusetts winters. For it me it’s a soliloquy for depression. We can read these last lines as the depiction of a final succumbing to depression. The last stand of reason collapsed as the mind falls further down and through the thickened boughs of a psychic hell. But I read differently. I feel these lines tell of breakthrough. They tell of depression leading to the breaking of reason yes, but that through that seeming ending of a reasoned reality alone, depth arises. Emily speaks of reaching something far greater than knowledge, and that is knowing itself: wisdom.

I have spent the years since my first encounter with depression fluctuating between states of wellness and states of extreme suffering. If it wasn’t for medication I wouldn’t be alive now tapping these keys, such was the force of the pain. However, if it wasn’t for my intuition that there was something more to depression, something more than the idea that my illness was a passive force that existed outside of myself, and if it wasn’t for my will to explore, and continue to explore as I do, other possibilities beyond medication, other opportunities for learning, I would never have found, as I suspect Emily Dickenson did, that depression could be my greatest teacher.

Depression has taught me about compassion, something I would have quaffed about in my younger years. Not the kind of token compassion, that says ‘ah sure Jaysus isn’t it terrible about so and so…’ Or the kind of compassion that rages against the world for all its apparent inequalities. Rather it’s the sort of compassion that feels the very depths of what it is to be human. It is heartfelt, and asks you to look at other beings without judgement because you understand now that you could never understand what it meant to be them, all their pain, all their glory; never.

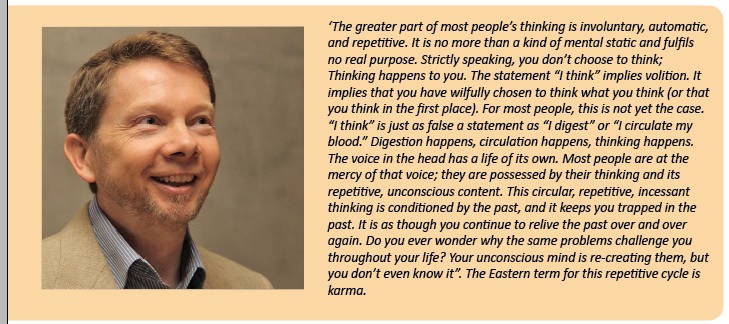

Depression has shown me the very depth of our human story. It has taught me that each and every single human being is looking out to the vastness of space on a cold clear night, deep beyond comprehension. Yet mostly we never live that, or ever even come to realise it. It lives in us like the unknown seed. Depression has taught me that the mind must not be believed, that it is conditioned, that it says things constantly like a little child with a tape recorder; over and over and over. Depression has shown me how our mind is predominantly negative, how its self-talk is so often self-harm. It has taught me that no peace can be found outside. No money, no fame, no book, no person, no future event in time and space will ever fill us up the way we hope it can. Depression has taught me that suffering is the ubiquitous human state, but that suffering can be transformed; turned as if by magic into understanding. Depression has taught me that the purpose of suffering may just be that. When the plank of reason breaks we come to learn, to grow, to suffer, to sow. The very way the farmer knows if he wants the seed to be strong he must cover it in soil, take the light away and shrouded in darkness then the seed grows strong.

The precursor for many of these realisations and for my movement from an almost ever-present state of suffering, to a point now where I experience calm, peace of mind, joy even, has been a steadfast practice of mindfulness, or what the author of The Power of Now, Eckhart Tolle calls ‘presence’.

Mindfulness is an odd word, and can often be misleading; its binary meaning one of which hints at a mind that is ‘full’. When in actuality with mindfulness practice what we experience is the exact opposite. What the Buddha called our natural state arises. A mind emptied of the frantic noise. One that is at peace, tranquil like the lake on a clear summers morning with only ripples of thought appearing when needed. Rather that the almost constant din of wave after wave of thought that almost everybody experiences as ‘their’ mind.

As a culture we have become so addicted to thinking that we do not even realise that thought has taken us over. It dominates us to such an extent that we no longer realise there is another aspect to us other the noise-making mind. We are unaware that something else within exists; namely attention. When we become present in the moment and the mind subsides we realise we are not our minds, we are something far wider, far deeper, far nicer! It is my steadfast belief that mindfulness, or what I prefer to call presence, is absolutely essential in helping people recover from depression. When our mind becomes still through presence practice, we can over time break the vicious cyclical nature of negative emotion and negative thinking. What remains then is often just the physical sensations of pain. I know this because I have experienced it first-hand. Most often now when I experience depression and anxiety I experience physical sensations predominantly and the crippling stories that in the past played like broken records in my mind never take hold. Eckhart Tolle’s quote above is pertinent.

When we provide tools for people to confront their pain, to deal with it in a real and progressive manner, we are providing them with opportunities to grow and become more compassionate, more caring, more productive citizens, we are helping them break the cycle of karma and to effectively create “A New Earth”. When we medicate to eradicate we deny growth. The author Chuck Palahniuk suggests the lack of a world war in our time is significant, he says “Our generation has had no great war, no great depression. Our war is spiritual. Our depression is our lives”. If we can live through our depression rather than just suppress it, we can perhaps come to realise its transformative power, as I’m sure many have. This does not mean medication is not a tool we can use, it is. But used alone, and particularly over long periods the evidence is beginning to suggest it might inhibit our ability to overcome and learn from depression. Every single person’s depression requires its own approach, unique to the individual. There is no one fix-all cure and currently we are failing sufferers of depression by medicalising to the determent of curing. Depression was once the quiet melancholy that left the lady of the house submerged in her quarters, far from the author’s pen and the protagonist’s intentions. It is now, in the age our great spiritual war, reaching epidemic proportions. Mental illness and depression is on the rise.

Severe, disabling mental illness has dramatically increased in the United States. “The tally of those who are so disabled by mental disorders that they qualify for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) increased nearly two and a half times between 1987 and 2007 — from one in 184 Americans to one in 76. For children, the rise is even more startling — a thirty-five-fold increase in the same two decades,” Martin Seligman, once president of the American Psychological Association, reiterates this trend. He discovered two astonishing things about the rate of depression across the century. The first was there is now between 10 and 20 times as much of it as there was 50 years ago. And the second is that it has become a young person’s problem. He says, “When I first started working in depression 30 years ago … the average age of which the first onset of depression occurred was 29.5 … Now the average age is between 14 and 15.”

The World Health Organisation projects that by 2020 depression will be the second leading cause of disease in the western world. They also predict a 50% rise of depression in young people. Niall Breslin spoke extensively on this point in his excellent recent address to the Oireachtas. His impassioned speech encapsulated the suffering of our youth and the urgency required in helping them. Our generation’s legacy; the world that we will hand to our children, will be a world filled with challenges. It seems probable now that catastrophic climate events are but a matter of when and not if. It seems increasingly likely also that we will hand over to our children a defunct, terribly unequal, and impotent economic system.

However, these things may be surmountable, the human spirit runs the roads of defiance, but not if we fail provide the tools for our children to navigate the rising storm of their internal world.

Marty Sheridan lives in Wicklow and works as a writer and a teacher. He also runs workshops in mindfulness and presence practice. These workshops are centred predominately around the work of Eckhart Tolle.

Marty Sheridan lives in Wicklow and works as a writer and a teacher. He also runs workshops in mindfulness and presence practice. These workshops are centred predominately around the work of Eckhart Tolle.

If you need any information about upcoming events, you can contact Marty at [email protected]

Latest Issue

Upcoming Events

-

17/04/2020 to 26/04/2020

-

18/04/2020

-

23/04/2020

-

15/05/2020 to 23/05/2020

-

16/05/2020 to 17/05/2020

Recent Articles

Article Archive

- November 2012 (3)

- December 2012 (1)

- January 2013 (7)

- February 2013 (6)

- March 2013 (7)

- April 2013 (7)

- May 2013 (7)

- June 2013 (3)

- July 2013 (7)

- October 2013 (2)