I, a Stranger and Afraid - on suffering and suicide

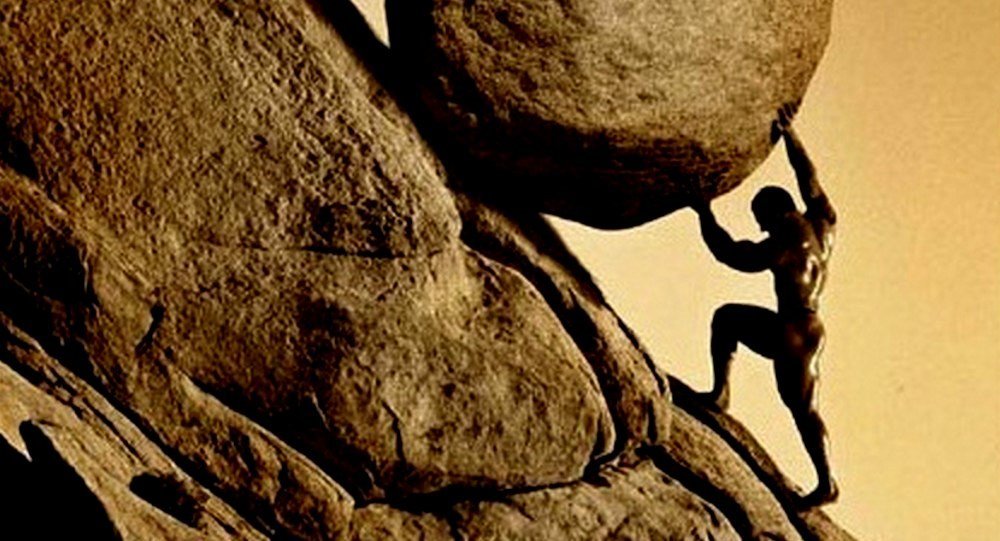

In Greek mythology, King Sisyphus, upon acts of deceit and treachery, is condemned for eternity to roll a large boulder up a steep hill. Precisely at the moment he reaches the peak Zeus enchants the boulder to slip from his grasp and it tumbles to its place of departure, and so too Sisyphus. And so he must begin again, and again…and again, consigned to an eternity of fruitless toil, all his efforts devoid of meaning and beset by pointless suffering and frustration. This is the fate of Sisyphus.

There is a truth at the core of this ancient myth that any human who has lived and lost can perhaps recognise. Life at times has a quality of feeling quite like the efforts of that forlorn Greek king. Things somehow feel perpetually out of our reach. So often we feel on the verge of something, of arriving at our goals end to reap what we’ve so arduously sown, relationships, money, jobs, health, or god forbid that heathen happiness. Yet just as we feel progress coming, like Sisyphus things seem to slip from our grasp. More often than not, life interrupts our well laid plans with some boulder of its own, and down we go. At other times we may reach the peak. We achieve a goal, we are successful at this or that, or worse even we become famous.

Invariably what happens then is rather strange. Emptiness arrives. The so long yearned for thing reveals its shapeshifting nature and our human ache returns. If this were not the case, the pillars of our ideals today; the musicians, the artists, the actors and actresses or even the demi-gods of wealth would emanate connectedness, peace and joy; love even. Yet they don’t. And from a certain vantage it is rather easy to argue they are miserable. More miserable than lowly me and you perhaps. Drug and drink addled, addiction and psychiatry prone, divorce bound. Fame is like a poisoned chalice. Yes, they have money and adoration. Yes, they are creatively recognised. Yet somehow the toll of success weighs heavy and far too often they die young.

There is a phenomenon in human nature which keeps these truths out of our awareness, and a clear majority of our culture are hoodwinked by erroneous ideals. Success, notoriety, recognition, money, they promise everything but deliver little of what the human heart truly desires. If we believe in the ‘one day’ the struggle pretends to keep the ache from our heart. What we fail to recognise then is that horizons are illusions, they can never come. Our pain will return despite our unwillingness to face it, and so we begin again. Not unlike the efforts of our Greek friend.

Technology and social media now allow us to live out our ideals and fantasies on a moment to moment basis. Facebook is a plethora of all that is supposedly good, and a vast barren quarry of anything that is real. The persona rules supreme here, and through the screen we can safely conjure the magic of who we want to be rather than who we are. There is no human contact to challenge these spells. In isolation, our opinions solidify and the horizon becomes voluminous. Reality becomes whatever you want it to be. Yet despite our magic tricks unease is growing.

In this generation, more than any other loneliness and unhappiness in all its guises undergoes amplification. I recently read somewhere that in the UK 1 in 4 women under the age of 25 self-harm. This shocking statistic unveils the impossible ideals of our culture. Young women cut off from their uniqueness and their essential qualities. In an act of both self-hate and an attempt at re-connection they bleed to feel real.

Human beings are social creatures. Here in lies the irony of social media. There is nothing social about it. Empathy, understanding, acceptance and belonging all occur through physical community. In a second-hand world played out alone with a screen nothing but image can reign. Persona steps into the fold and our essence connection is severed. The strange irony of this digital age is that we are simultaneously more connected and more disconnected than ever before.

It is wonderful to watch a small child play. To recognise how at home they feel in the world, they are essentially themselves. Equally a dog. This extraordinary animal is always available to Life as it is, to its essential nature. As we age however our connection to home undergoes a profound change. Our essential nature slips into the background and the infamous lines from Housman’s poem becomes our dictum…

And how am I to face the odds

Of man’s bedevilment and God’s?

I, a stranger and afraid

In a world I never made.

Our own disconnected state is the malady of the wider world. All the conflicts we see on the screen are all but the same conflict raging deep in our hearts. The election of US President Trump is a shock to us all, and the thought of his office depresses and scares us. Yet many are shocked when they see their own personal dysfunction for the very first time, I certainly was. The human psyche keeps our darkest sides lurking in the shadows, out of the spotlight of our conscious world. Trump lives in these darkened corners of all of us, to varying degrees of course. He couldn’t have risen to power had he not. His nationalism and exclusion is our selfishness and our lack of compassion; his preposterous wall are our own personal walls. Walls which keep our shell intact and our separation secure.

When we continue to live in this disconnected state we live in the addictive grip of the material. We need more and more of everything. We need more because what we are attempting to connect to for fulfilment can never fill us. Mr Trump has it all yet like a bold child he craves attention, craves recognition. We all need more because what we are really looking for runs the roads of another world. If we can turn inward toward our essence, to the intelligent source behind the veil of the material, our addictions will fall away by themselves, our need and our greed will disappear. There will be no power and balance may return to the world.

The French philosopher and political activist Albert Camus was a voice of sanity in one of the darkest times in humanities history, a time when the Germanic nightmare threatened to draw its black curtain over the soul of the world. A time that many fear we are on the borders of again. Around this time, he wrote a famous essay after our self-same Greek king entitled “The Myth of Sisyphus”. It’s opening lines…

“There is only one true philosophical question”, says Camus, “and that is suicide”.

This statement confounds us when we hear it first. Yet below the surface of what Camus is saying lay fundamental questions to the human problem. Is Life worth the pain? What is the point of all the suffering? And if there is no point to the suffering, should we not just spare it all and end our lives?

Suicide is still one of the great taboos in our societies. In bygone eras victims were buried without rites of passage. As if their God was not a loving God or a forgiving God. A vision made in Man’s image alone. We have made progress from those dark days, But how much? In certain societies suicide is still against the law. This does little though to stop its rising tide. In India attempted suicide is punishable by law. For all that India has one of the highest rates of suicide in the world today.

When a person takes their own life, it creates impenetrable dismay. It seems as if a sacred contract is broken and our lack of understanding breeds the breath of fear. Our fear manifests in the under-reporting of attempts and deaths. In coroner’s willingness to declare ‘death by misadventure’ in our own unwillingness to speak, and its opposite; towns whisper like wildfire. There is also a narrative of hysteria around suicide which exists in an effort against the normalizing of suicidal behaviour. Some would argue all these reactions are healthy ones, and that a battle against suicide must be waged. Yet none of our natural reactions are stemming the tide. Every 40 seconds on this planet someone takes their own life. When you have finished reading these words 50 people will be dead. Conservative estimates by the World Health Organisation suggest by 2020 we will be losing upwards of 1 million people every year to suicide.

The reasons human beings take their own lives are complex and extremely varied, yet there are common factors. There is mostly always present a deep sense of hopelessness, and a very real physical and mental depression. Thoughts are hopelessly out of control, and these thoughts drive people to the edge and beyond. Invariably suicide victims have been dealing with these thoughts and feelings for a period before they seek help, or tragically seek an end.

In particular, there are two casual factors to suicidal behaviour. Suffering is the first. There is no denying the pain and suffering that brings people to the doors of suicide. However, this suffering is often compounded and deepened from a belief that human pain is pointless and somehow self-created, and that consequently we have failed at this thing called ‘life’. This belief in failure is one of the reasons why suicide affects men predominately. Success or failure are still very primal forces in the male psyche. Shame comes then and an unwillingness to seek help, stemming from the belief that society will not understand. The second factor underpins all of this and it is one that affects all human beings; the innate belief in everything that the mind says.

In the awe-inspiring recent Planet Earth 2 series there featured a tiny long-eared bat who lives in the deserts of Palestine. Each night this bat must rise into the nocturnal battlefield and hunt. Food is not readily available in this the harshest of environs, so this bat must face and overcome the deadliest of foes; the scorpion. Our brave bat must do battle, and win, with a species which strikes fear into the heart of most humans. She must do this not only once or twice but four times each night if she is to survive. Just to make these conditions even more ridiculous our little bat is blind. This bat’s life is so harsh it borders on the ridiculous, yet she cares not. I have little doubt that if the bat had a human mind she would contemplate Camus’s statement and end her life. What would be the point?

Human beings are one of the only species we know of on this planet with the ability to think abstractly. We are also the only species who take our own lives. The human mind is a wonderful product of evolution. It has produced vast wonders yet now it seems the mind has outgrown its host and taken control. When put to a task the human mind is at its best. Yet when the task is over we cannot put down our minds as a workman would his tools. The mind has assumed an identity, a ‘me’, and so we believe it’s every word. For most people the mind produces varying degrees of neurosis but for some, and these are an increasing proportion, the mind turns on them. We call this mental illness yet everybody experiences the negativity of the human mind it is only the degrees that vary.

The ancient wisdom traditions who spent countless years observing the mind came to realise that this voice in our head, the ‘me’; the identity the mind has assumed, is an imposter. It is a ghost with a particular palette for dysfunction. Our little Bat faces extreme challenges. Like lightning strikes the scorpion stings lash her face as she blindly attempts to overcome her foe. What is the point of her ridiculous struggles? Evolution of course. Through the force of extremity this Bat will eventually produce some growth. The ability to see perhaps, and consequently move to a less challenging prey. Without the struggle however nothing will come.

The very same is true of human pain. It offers us the same promise of growth. Which is its very function. Yet nowhere in our culture is this understanding apparent. Instead we are led to believe the opposite. That suffering is bad and the possibility of avoiding it is down to us. This, is a great un-truth. If the reality of suffering were taught to children their future selves may face darkness with an entirely different perspective. If the reality of the human mind and its assumed identity, its tendency to create dysfunction, and our inability to find the off switch, were all faced and overcome it is my belief that suicide would practically disappear.

On a wet dark night in the early days of December my partner’s brother took his keys and left his young family on an errand. He never came back. He drove his car into a river and ended his life. Jackie was 39 years old, the same age as myself. He had been suffering with depression for a short period prior to this, but most likely he had been experiencing this for longer. The help was too little too late. I understand how he was feeling. I have stood at the edge myself. I have stared into the precipice. I have felt the kind of pain that makes escape seem almost necessary. Yet I’m still here and Jackie is gone and I wish I could have told him what I know now. Perhaps it would have made a difference, perhaps not.

The tidal wave of devastation that was left in Jackie’s wake is impossible to breach with mere words. I didn’t know Jackie well but I saw what he meant to people. It was etched on the faces of friends and family. Jackie touched so many lives and this is his enduring gift to the world, and so Joyce’s words go, “so sad and so beautiful, so beautiful and so sad”. Suicide leaves family and friends in a black dark void. It moves outside of the parameters of grief and it will I suspect, always feel to those left behind as if it should not have happened. Yet we must strive toward some acceptance, toward some semblance of surrender, to understanding. Otherwise Jackie’s pain becomes his legacy, and he and we are so much more.

So, what can we say to the almost 1 million people who will take their lives next year, what can we do to help them? We can start, as my Father would say by “cutting the shit”. By this I mean dropping the awful pretence with which we all engage that any of us are ‘ok’. Life is hard here, as it is supposed to be. There is a place for being ‘ok’ in the human experience of course, a place for securing our needs. But at a more fundamental level what we are engaged in here is evolution, and essential to that process is facing both internal and external challenges often extreme in nature. By embracing and accepting our challenges in the knowledge that they are necessary rather than a failure, deep suffering may be avoided and instead we may grow, we may evolve.

We can start by sharing our human suffering with one another. We can take our pain in each other’s arms and hold it there as the one human pain that it is. In this act a deep compassion for our human family may arise. Stigma may disappear. We can start by teaching our children about the nature of the human mind, and teach them practices to help them maintain their essence connection above the noise and the allure of the world. When darkness comes then the mind may not follow.

Looking back to our good Greek King now we see that perhaps like Sisyphus we are not meant to reach a destination here, this is not our fate. Instead it is within the struggle, the process, and the pain, where the human heart is forged. In that knowing then lies our greatest power, our power to overcome.

Marty Sheridan lives in Wicklow and works as a writer and a teacher. He also runs workshops in mindfulness and presence practice. These workshops are centred predominately around the work of Eckhart Tolle.

If you need any information about upcoming events, you can contact Marty at [email protected]

Latest Issue

Upcoming Events

-

17/04/2020 to 26/04/2020

-

18/04/2020

-

23/04/2020

-

15/05/2020 to 23/05/2020

-

16/05/2020 to 17/05/2020

Recent Articles

Article Archive

- November 2013 (2)

- December 2013 (1)

- January 2014 (2)

- February 2014 (2)

- March 2014 (2)

- April 2014 (4)

- May 2014 (2)

- June 2014 (1)

- July 2014 (4)

- August 2014 (1)